| The 8th Dwarf |

Gorbacz wrote:

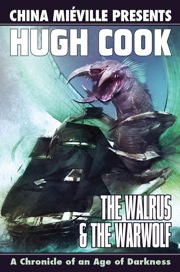

drow wrote:heh... my first impression of the cover was, "DUDE! ALIEN RIDING A SNOWMOBILE! AWESOME!" but it now appears to be merely looming over a sailing ship. oh well.+1

I have read most of the W - W books, they are well worth reading. They are refreshing in their originality. Cook bends the usual fantasy tropes 90 degrees and comes up with the most insanely wicked and funny stories.

There is much, much more interesting stuff than Aliens riding snowmobiles in the books.